Design Brief

1. THE CONTEXT

The Deer Cave of Porto Badisco (La Grotta dei Cervi di Porto Badisco), discovered in 1970 near Otranto in Salento, is one of the most extraordinary prehistoric sites in Europe. Here, more than 7,000 years ago, communities left the largest and most complex ensemble of Neolithic wall paintings known on the continent. For a long time, the cave was a true underground sanctuary, frequented by groups even from distant regions of the Mediterranean.

1.1 The cult dedicated to the Great Mother

Archaeological research indicates that the cave was linked to an important prehistoric cult: that of the Great Mother, a female deity venerated in many Mediterranean cultures. Indeed, in the Near East, the Balkans, and the Greek area, numerous statuettes have been found representing her as Lady of Life, Ruler of Death, or Goddess of Regeneration, protector of the cycle of humans, plants, and animals. The very structure of the cave, with corridors dozens of meters deep, reminded the ancient visitors of the womb of the Goddess, a symbolic belly in which to perform ceremonies related to the fertility of the fields, rebirth, and the protection of the community.

Many traces of ritual practices remain: remains of hearths, vases placed inside natural cavities or holes dug specifically, animal offerings, carbonized grains, ornaments and tools in various materials, even from far away. All these elements indicate that the cave was a chosen place for important rites and shared ceremonies.

The ancient visitors did not limit themselves to entering the cave: they transformed it. Inside the tunnels they built dry-stone walls, carved steps, and created artificial embankments. These modifications demonstrate that the cave was not a simple natural shelter, but a ceremonial complex designed in a unitary manner and used for centuries. The internal paths, perhaps of an initiatory nature, led to the darkest and most hidden spaces, where the most secret rites were probably celebrated. It is possible that ritual deer hunts also took place during these ceremonies, a kind of initiation trial aimed at young archers.

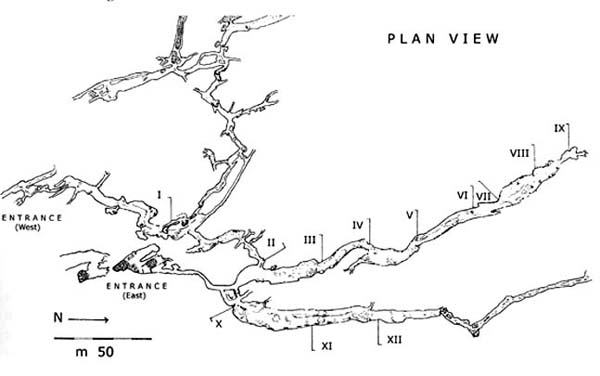

Roman numerals indicate the Zones (remake from Graziosi, 1980)

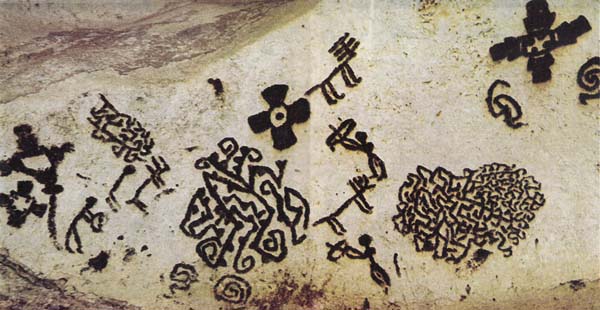

(ph. ML Leone, 2009)

1.2 The paintings

The Deer Cave extends for over 700 meters and features three main corridors, divided into twelve zones. The paintings are gathered in 81 groups, made with pigments derived from subfossil guano (brilliant brown), clays and ground bones (yellowish brown), and ochre (red). Most images are abstract: spirals, sinuous lines, complex motifs, and "arabesque" shapes. Some figures derive from increasingly stylized human bodies, eventually becoming almost unrecognizable symbols.

Figurative scenes are less frequent but very evocative: deer, men armed with bows, and dogs in hunting episodes, often interpreted as ritual or mythical moments. This choice of representing the symbol more than reality marks a profound difference compared to Paleolithic art.

1.3 A place of meeting and alliances

The ceremonies held in the cave probably involved different groups from distant territories. This sanctuary was likely the place where pacts, alliances, and exchanges of gifts were made, under the protection of underground deities. Materials from distant areas reinforce this idea.

1.4 The discovery

The cave was discovered on February 1, 1970, by speleologists of the “Gruppo speleologico salentino de Lorentiis” of Maglie (LE), during an excursion in the inlet of Porto Badisco. One of them noticed cool air coming from a crevice and, after removing surface material, uncovered the first deer representations. They first named it “Grotta di Enea” but later “Grotta dei Cervi” due to the many deer hunting scenes.

1.5 The Exhibition at the Aragonese Castle in Otranto (LE)

The cave is not open to visitors because its delicate humidity and temperature conditions would be altered by human presence. Access is only allowed for study or monitoring with special authorization.

In 2004 a project began to create a high-resolution 3D model of the cave. Since 2016, a 3D virtual tour has been available at the Aragonese Castle of Otranto, along with life-size reproductions, ceramics, and pintaderas.

Starting September 23, 2025, the exhibition “I luoghi della Preistoria e la Grotta dei Cervi” (“The Places of Prehistory and the Deer Cave”) will present prehistoric materials from the Otranto area, alongside finds from the Deer Cave. A large room is entirely dedicated to the cult site, with ceramics and artifacts linked to shamanic and fertility rites (Late 7th - Early 4th millennium BC), concluding with materials from the Metal Age. The itinerary includes the projection of the 3D cave model.

1.6 Institutional Goal

The institutional goal is to increase engagement with a site of exceptional cultural value, expanding its national and international visibility and strengthening the institution’s capacity to reach broader and more diverse audiences. The project also aims to capture the interest of the many visitors who travel to Salento each year, offering an innovative experience that makes an otherwise invisible heritage recognizable and memorable. Through this digital valorization strategy, the initiative further seeks to position itself as an experimental model capable of attracting new funding, both public and private, by demonstrating how immersive technologies can amplify the cultural and social impact of an inaccessible heritage site, thereby encouraging additional investment in research, documentation, and outreach activities related to the cave.

1.7 Cognitive Goal

The cognitive goals of the project aim to foster a deep and informed understanding of the Deer Cave, its pictograms, and the Neolithic cultural context in which they were produced. Through a structured digital experience, users are guided in developing interpretive abilities that help them recognize shapes, symbols, and visual narratives, connecting them to the lifeways and belief systems of the communities that once frequented the site. The initiative seeks to transform simple curiosity into active learning, stimulating historical reasoning, critical reading of images, and the ability to link material evidence with the ritual and social meanings of the Neolithic context.

1.8 Star Assets

The Star Assets of the project lie in its ability to transform an inaccessible and otherwise invisible archaeological heritage into an engaging and innovative digital experience. At the core of the proposal is the development of a video game that integrates a 3D model of the Deer Cave, allowing users to virtually explore the site and interact with its pictograms.

The experience is built around some of the cave’s most iconic elements: the shaman pictogram, among the most enigmatic and symbolically charged images of the sanctuary; the hunting scenes depicting deer, which not only represent one of the most dynamic narrative sequences in the cave but also inspired its modern name; and the wall of handprints, a powerful testament to ritual practices and identity-marking gestures performed by Neolithic visitors. These highlights guide the structure of the interactive experience and serve as narrative anchors throughout the game.

Conceived as a digital resource supporting the museum exhibition, the game functions as a powerful learning tool: it enables users to understand the meaning of the wall representations, situate them within their Neolithic cultural context, and bring diverse audiences closer to a site that cannot be visited physically. Through this combination of virtual reconstruction, interactive storytelling, and technological accessibility, the project enhances the historical and symbolic significance of the Deer Cave, increases public awareness of the site, and strengthens its presence within the collective imagination.

1.9 The Audience

The project addresses a broad and varied audience, including curious visitors, school groups, and enthusiasts of history and archaeology. The digital experience is designed to be accessible even to users who are unfamiliar with the Deer Cave, offering intuitive tools and immersive content capable of engaging both newcomers and more experienced individuals.

2. THE AUDIENCE

The project is aimed at all those who wish to deepen their understanding of the Deer Cave: both local visitors interested in rediscovering the history of their origins, and the many tourists who travel to Salento every year, including foreign visitors who often ignore the existence of this site despite its European relevance. For this heterogeneous audience, made up of curious visitors, traveling families, students, and enthusiasts of history and archaeology, the video game experience represents a unique opportunity to explore a place that is normally invisible and inaccessible to the public, transforming the visit into a moment of immersive and memorable learning.

Motivations: Visitors are drawn to the experience because it offers a form of time travel capable of connecting them with a remote reality. The Deer Cave, inaccessible and little known, represents a “cultural mystery” that immediately stimulates curiosity, especially among visitors who do not know what to expect from the exhibition but wish to be surprised by something unique, unusual, and out of the ordinary. The pleasure of discovery, combined with the opportunity to explore a prehistoric site available only through digital means, constitutes a strong motivational element.

Barriers: The main obstacle for visitors is the total physical inaccessibility of the cave, which prevents any direct contact with the site. On a practical level, accessibility barriers may arise: different levels of familiarity with prehistoric history and the risk that a highly specialized theme may be difficult to understand without adequate digital mediation. Moreover, for tourists visiting Otranto for short periods, a lack of time may represent an additional barrier to engaging with complex or text-heavy content.

Another aspect considered during the design phase concerns the physical or cognitive needs of some visitors, who require suitable tools to fully enjoy the experience, a condition not always guaranteed in traditional museums. For this reason, the digital experience has been conceived to be clear, guided, and inclusive, minimizing obstacles for all users. To further support this, a tactile component has been introduced: visitors can touch physical replicas of archaeological finds from the cave, which also appear in their digital version within the video game. This multisensory element allows all users, regardless of ability, to establish a more immediate and accessible connection with the archaeological heritage.

Capabilities: The experience is designed to be accessible to a broad audience with varying levels of technological familiarity. To fully benefit from the activity, it is helpful for visitors to possess basic skills in using websites, social media, and simple gaming systems, abilities that are now common among adolescents, adults, and families. It is not necessary to be an expert gamer or to have specific archaeological knowledge: the interface is designed to guide users step by step, fostering intuitive and immediate learning. The project leverages users’ ability to recognize visual patterns, interact with digital content, and follow simple instructions, transforming initial curiosity into an active, understandable, and engaging experience.

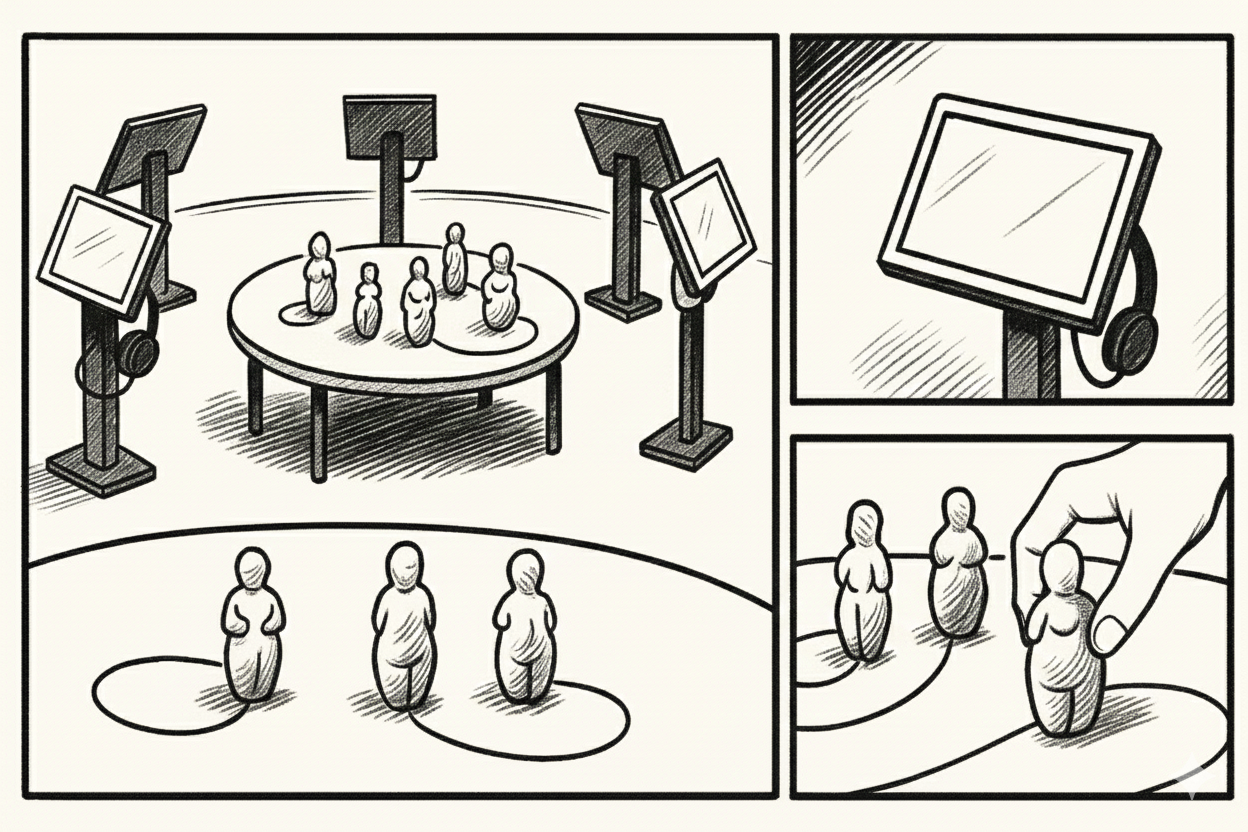

Devices: The experience is designed to be enjoyed through stations equipped with tablets, arranged in a circle within the dedicated room, symbolically recalling the presence of the five speleologists who discovered the cave.

Each user interacts directly with their device, which features a simple and immediate interface designed to be intuitive even for those without advanced technological skills. Only a basic familiarity with tablets is required, a competence now widespread among most visitors, as the game guides the user step by step, minimizing the need for external instructions. The choice of the tablet also ensures an accessible, comfortable, and immersive experience, allowing each visitor to engage autonomously, naturally, and without technological barriers.

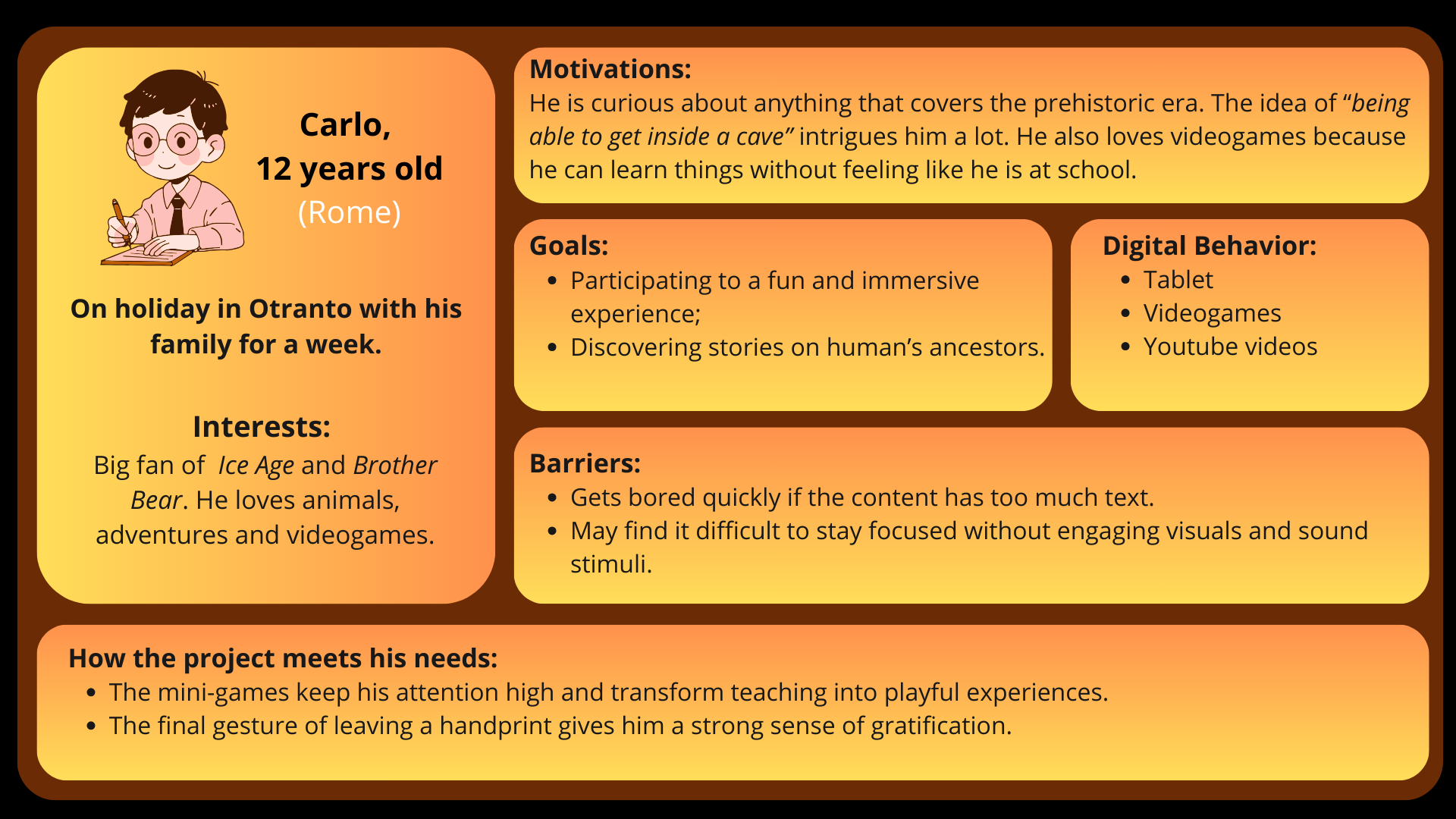

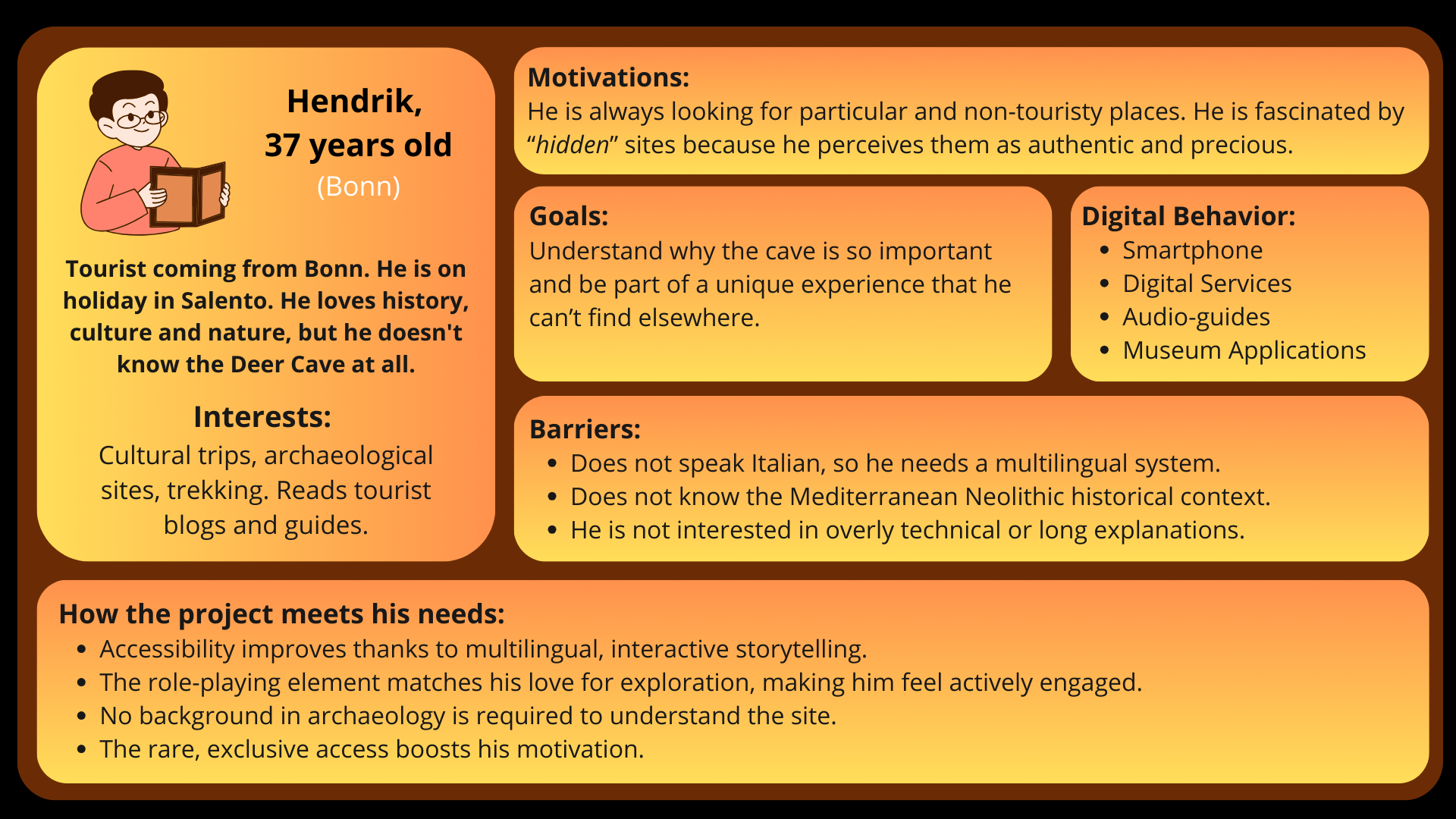

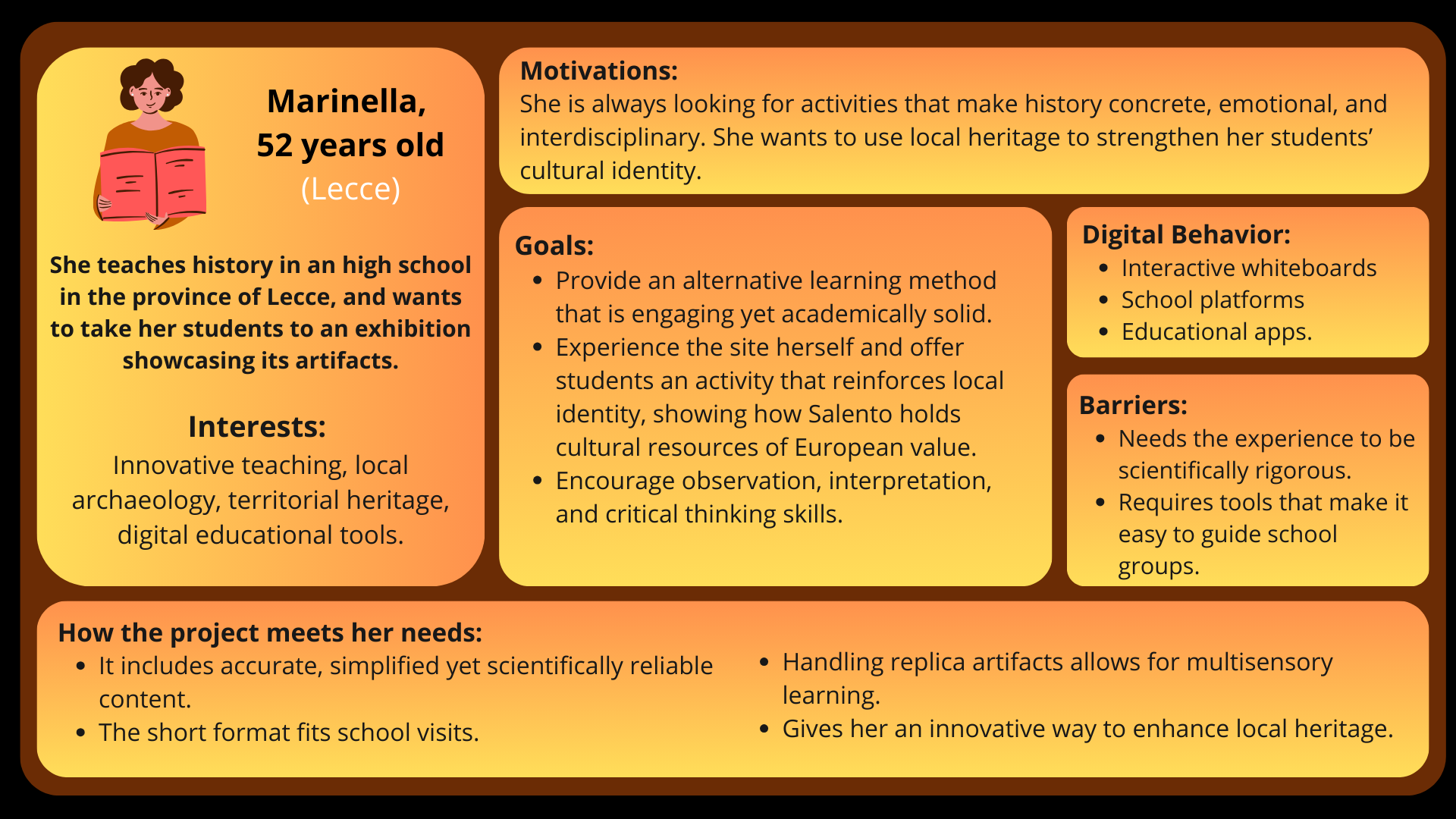

At this stage, three user personas were also identified, useful for representing different visitor profiles and for guiding design decisions related to the digital experience in a more targeted way.

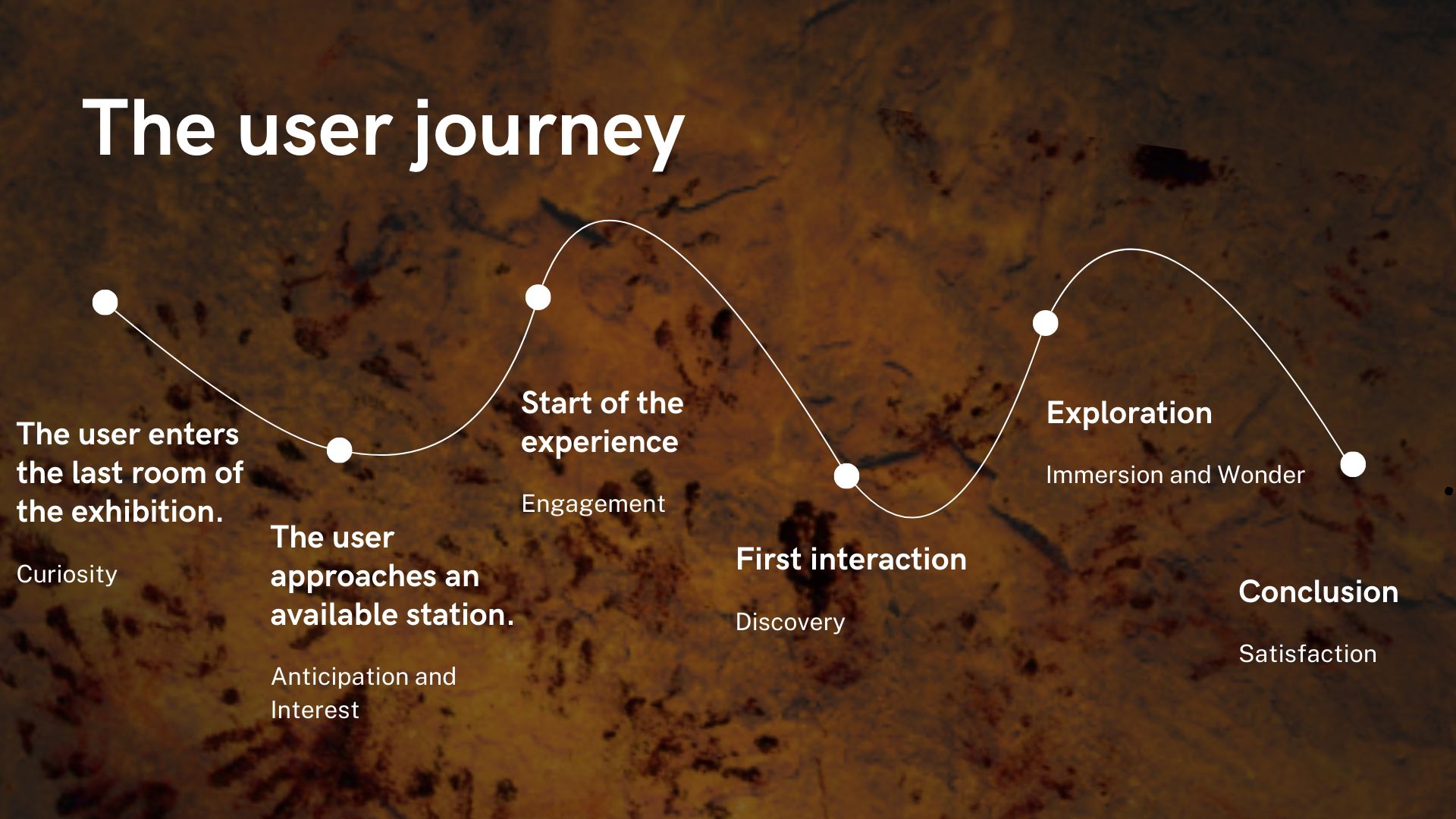

To better illustrate how visitors interact with the experience, the following image presents a simplified user journey. It visually summarizes the key steps that each user goes through, from the moment they enter the final room of the exhibition to their progression through the digital exploration of the cave, highlighting actions and emotional responses throughout the process.

3. THE CONCEPT

The main challenge lies in providing an immersive experience capable of compensating for the complete impossibility of physically visiting the cave. At present, the only way to “enter” the Deer Cave is through the 3D reconstruction created by the University of Salento, available in a dedicated room of the exhibition “I luoghi della Preistoria e la Grotta dei Cervi”. To this physical barrier is added the difficulty of attracting audiences who do not usually engage with prehistory or archaeological displays, such as occasional tourists, families, and non-specialist visitors, as well as the interpretive complexity of the Neolithic pictograms, which are often difficult to understand without appropriate mediation.

To address these issues, the project aims to integrate the existing 3D model into a narrative and interactive structure that enhances immersion and fosters engagement. A well-designed digital experience can in fact tackle all three problems simultaneously: on the one hand, it mitigates, as far as possible, the limitation posed by physical inaccessibility; on the other, it transforms complex content into intuitive and engaging forms, stimulating interest even among those unfamiliar with prehistory. The combined use of a video game, the tridimensional reconstruction, and the accompanying tactile experience allows users to “enter” the cave virtually, explore its symbols, and interact with them in a guided and progressive manner, reducing cognitive obstacles and broadening participation among a diverse audience. The experience does not aim merely to inform, but to generate wonder, immersion, and active involvement.

To achieve these goals, it will be essential to support the project with an effective communication strategy capable of ensuring visibility and reaching as broad and diverse an audience as possible. In exploring this aspect, we analyzed various online reviews concerning the Deer Cave, which reveal a fragmented and unclear communication landscape with significant room for improvement. Here are some selected reviews:

As becomes evident, many visitors are unaware of the cave’s inaccessibility and of the alternatives offered by current outreach initiatives. It is therefore crucial to implement clearer and more consistent communication that immediately informs visitors about the actual possibilities of access and highlights the digital and immersive experiences proposed. A coordinated promotional effort across the territory, starting from the municipality and in collaboration with the Aragonese Castle, the venue hosting the exhibition, represents a key step in building awareness, managing visitor expectations, and supporting a more informed and satisfying experience.

From a musicological approach, the soundscape draws inspiration from the evocative voices of the Sirens in Black Panther: Wakanda Forever, characterized by deep, enveloping, and quasi-ritual vocal qualities. These sounds do not seek to faithfully reconstruct a Neolithic acoustic environment, but rather to evoke a subterranean, mysterious, and archaic atmosphere capable of enhancing the immersive perception of the cave and emotionally supporting the visitor’s journey.

The themes selected as case studies derive directly from the symbolic elements present within the Deer Cave. The visual and narrative inspiration includes references to Brother Bear for its connection between human figures and the spiritual world; the veneration of the Great Mother Goddess, a central figure in the cave’s paintings and Neolithic ritual context; and initiation rites, evoked both by hunting scenes and by the famous wall of handprints, interpreted as identity marks or ritual proofs. Indeed, as will be explained in the following sections, the ultimate goal of our digital experience is the symbolic act of placing one’s own hand on the wall, a gesture that echoes this ancestral practice and allows visitors to feel part of a human continuity spanning millennia.

4. REQUIREMENTS

To achieve the institutional, cognitive, and experiential goals of the project, a series of requirements have been identified and organized according to the MoSCoW methodology, an important component of agile development.

Must

Mandatory requirements, essential for the project to function:

- The system must integrate the 3D model of the Grotta dei Cervi in a stable, navigable, and scientifically accurate way.

- The experience must be accessible through tablets arranged in the five dedicated museum stations.

- The video game must ensure a level of accessibility that allows visitors of different ages and technological skills to use it.

- The game must include content that supports the achievement of the cognitive goals, particularly the recognition of the pictograms and the understanding of their Neolithic context.

- The interface must be intuitive and guided, with clear instructions available in multiple languages.

- All content must respect the scientific accuracy of the archaeological and cultural data.

Should

Important and highly desirable requirements, though not strictly indispensable:

- The experience should include an immersive narrative that gradually guides the visitor through the discovery of the site.

- The system should include mini-games designed to assess understanding and maintain the user’s attention.

- The sound environment should create an evocative and atmospheric setting.

- The game should foster emotional engagement by incorporating symbolic themes of the cave, such as the Great Mother deity, initiation rituals, and handprints.

Could

Desirable requirements that would further enhance the experience if resources allow:

- Integration of additional content, such as optional in-depth materials for expert visitors or scholars.

- Possibility of offering a cooperative multiplayer version of the video game across the five stations.

- Development of the same experience with optional VR support, aimed at further increasing the level of immersion and expanding the educational and sensory potential of the interaction.

Won’t

Requirements that will not be developed in this phase of the project:

- The experience is not intended to replace educational activities or museum-guided tours, but rather to complement them.

- The game will not include dynamics that are inconsistent with the archaeological context.

- The project does not foresee, at least in this initial phase, the development of a full video game intended for commercial distribution or use outside the museum itinerary.

5. IDEATION

5.1 The user experience

The experience is designed to place the user in the role of one of the speleologists who discovered the Deer Cave. From the player’s perspective, the video game unfolds as an immersive and progressive journey: they enter an unknown environment, observe enigmatic pictograms, encounter the shaman, and face interpretive challenges that require memory, attention, and curiosity. The goal is to create an experience that blends discovery, narration, interaction, and learning, transforming the visitor into an active protagonist.

In our design, the user enters the room dedicated to the video game at the end of the museum visit, after having already acquired an initial cognitive understanding of the Deer Cave through the physical exhibition of artifacts and the projection of the 3D model. Entering this dedicated space represents a moment of transition: from the informative dimension of the exhibition to an experiential and immersive mode in which the visitor is invited to “get involved” and rework what they have learned. At this stage, the user also begins to approach one of the central themes of the experience: the need to develop a critical gaze towards representations that may not be immediately reliable. This aspect will be further explored in section 5.2, which addresses the concept behind the project.

The room contains five stations arranged in a circle, symbolically recalling the five speleologists who made the discovery. Each station is equipped with a tablet mounted on an adjustable stand, ensuring accessibility for users of different ages, heights, and abilities. The interface is designed to be intuitive and straightforward, allowing even those unfamiliar with gaming to navigate easily.

The experience also relies on multisensoriality: in addition to the immersive visualization of the 3D model of the cave and the evocative acoustics that recall a hypogeal environment, there is also a tactile component thanks to the presence of physical replicas of archaeological artifacts, which also appear in their digital form within the game. Through this combination of visual, auditory, and tactile stimuli, the experience takes on a strongly embodied dimension: the user does not merely observe, but acts, touches, listens, and interprets, engaging in a form of learning that is both cognitive and sensory.

To complete this journey, the experience culminates in a final reward: after solving the proposed minigames, the user is symbolically invited to add the imprint of their own hand to the digital wall that gathers those of the ancient frequenters of the cave. This ritual gesture, deeply rooted in the real practices documented in the Deer Cave, transforms the visit into a participatory and identity-building act, creating a direct emotional connection between past and present.

5.2 The Storyline and the Conceptual Framework

Before introducing the actual storyline, it is essential to clarify the spatio-temporal context that frames the narrative. The experience is set in Porto Badisco, Otranto, on February 1st of a year intentionally marked as XXXX. This choice is not accidental: the day explicitly refers to the real discovery of the Deer Cave, which took place on February 1st, 1970, while the year is deliberately left undefined.

This decision follows a strategy often adopted in video games when one wishes to avoid a precise temporal placement or evoke a setting suspended between past and present.

The main motivation lies in the narrative concept (Detective of the Past) that underpins the entire project: a contemporary world in which, partly due to the increasingly widespread, and sometimes improper, use of artificial intelligence, it has become progressively harder to distinguish what is authentic from what has been manipulated. This condition of uncertainty does not concern only the present, but also affects the way we interpret the past, making it more difficult to recognize, understand, and validate historical traces. Indeed, the video game integrates explicit references to this theme, encouraging the user to confront the fragility of the past and the need to interpret it critically.

Making the year deliberately indecipherable through the marker XXXX becomes a functional narrative choice: it allows the story to take place in a suspended time, not rigidly anchored to the past nor fully attributable to the present. This device preserves the connection with the real day of the cave’s discovery while allowing the storyline to incorporate thematic elements aligned with a more contemporary sensibility, such as interpretive uncertainty and doubt.

Leaving the year undefined therefore creates a flexible narrative space in which the historical and contemporary dimensions can coexist without contradiction. It is a subtle signal that immediately suggests to the user that not everything is perfectly fixed or stable, and that even the perception of time can be ambiguous, just like the images, memories, and interpretations the user will have to confront during the game.

The core of the experience, then, is not only the exploration of the Deer Cave, but the cultivation of a critical gaze capable of questioning what is presented, evaluating its coherence, and recognizing when something “doesn’t add up.”

The choice to use XXXX also has a communicative intention: to spark players’ curiosity. The fact that the real date is not disclosed immediately introduces a small enigma that leads the user to wonder about the reason behind the choice and, once the motivation is revealed, to more easily remember the authentic date of the discovery. Had the year 1970 been explicitly stated from the start, the risk would have been that the detail would go unnoticed; presenting it instead as a “hidden” element enhances its memorability.

As for the storyline, it unfolds during a speleological survey. A mysterious force pulls the five explorers into an underground cave system made of winding passages, whose walls are covered in enigmatic paintings. While the speleologists examine these figures, a shape begins to materialize before them: an ancient shaman, seated before a fire and engaged in what appears to be a ritual chant.

The shaman interacts with the speleologists, recounting the history of the cave and the profound cult devoted to the Great Mother, the deity of fertility, good harvests, the cycle of the seasons, and more broadly, all that concerns life and death. He invites the visitors to reconstruct the story of the cave alongside him, testing their attention to detail through a series of interpretive challenges. In doing so, the speleologists gradually become involved in the ritual dimension of the site: the shaman urges them to take part in the ceremonial offering to the sanctuary.

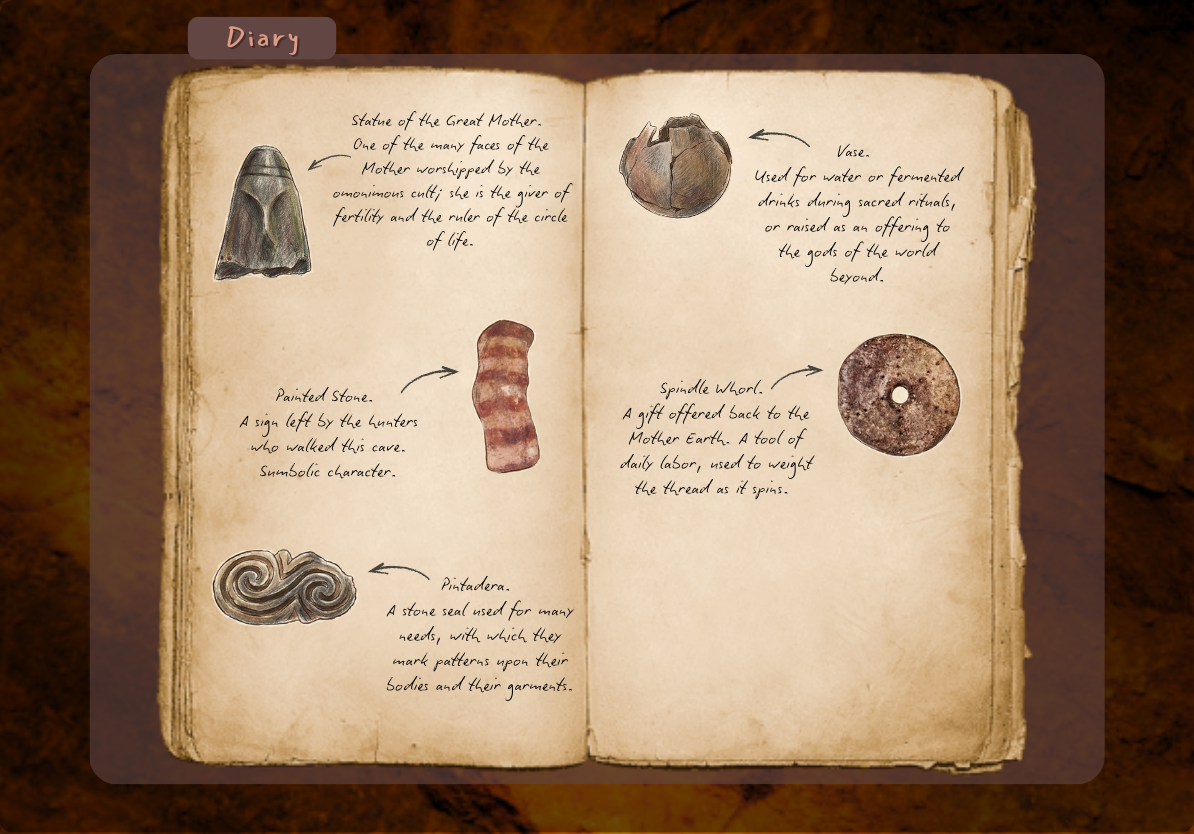

With the guidance of this ancient religious figure, the players learn the meaning of the five objects used in the ritual, information they can record in their personal diary, which they will carry with them once their journey into prehistory ends, as a symbolic trace of the knowledge they have acquired.

When the offering is completed, the fire blazes more intensely, almost as if signaling the explorers’ growing understanding of the Neolithic world. At this moment, three young hunters make their entrance, emerging from a corridor of the cave to give thanks to the goddess. They recount their successful deer hunt, depicted in the surrounding paintings. Here too, the speleologists must demonstrate attention and memory, helping the hunters reconstruct their story, now muddled by the shaman’s illusions, once again designed to test the visitors from the future.

At the end of this mission, the speleologists receive one final privilege: the chance to leave the imprint of their hand on a dedicated wall, echoing the gesture of the ancient visitors of the Deer Cave and symbolically marking their “initiation” into the knowledge of the site.

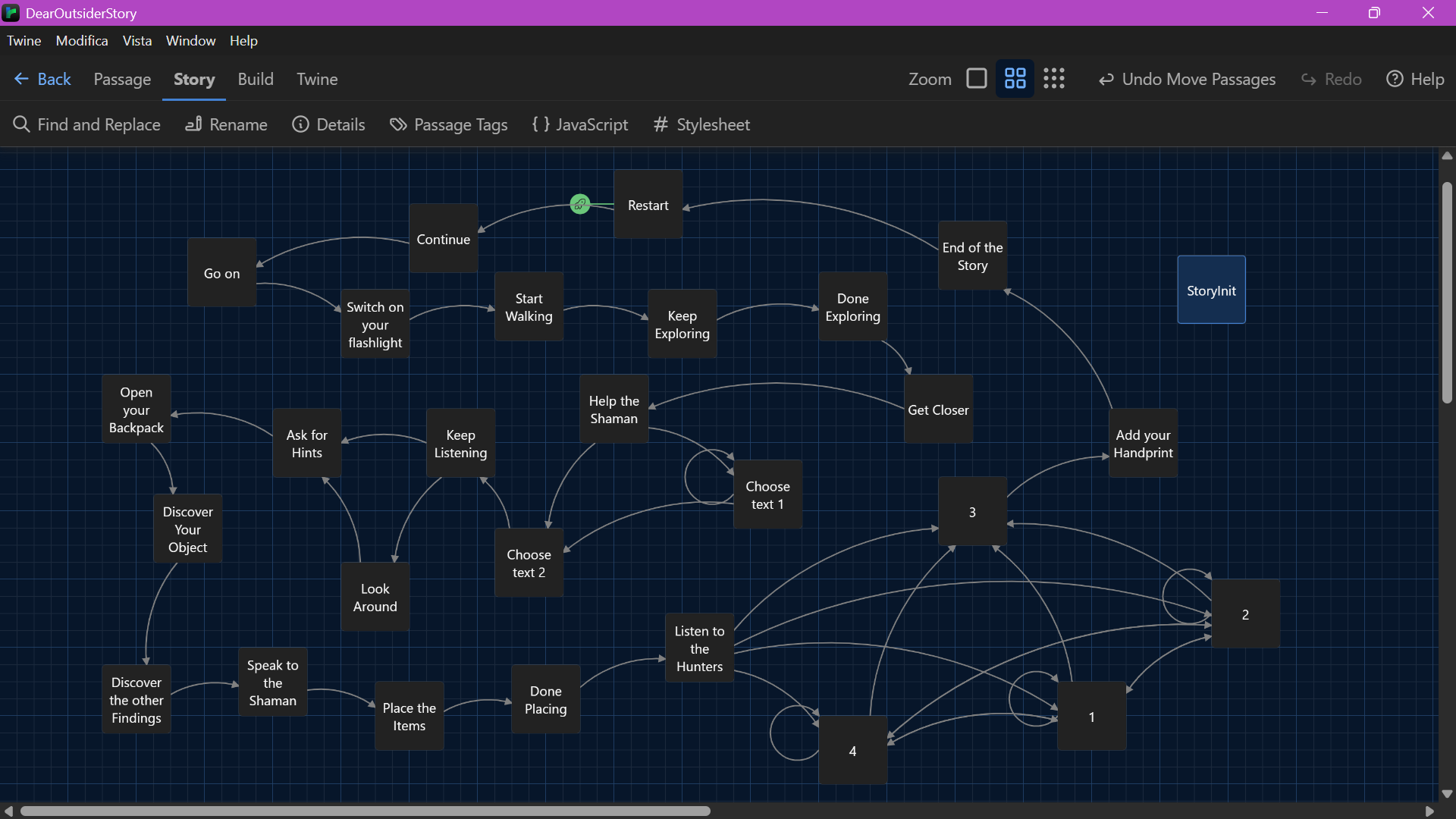

The following diagram schematically illustrates the narrative elements designed for the video game, as well as the interaction with the user:

5.3 The prototype with Twine

To complement the design work, an interactive narrative prototype was developed in Twine, used to model the narrative logic, branching paths, and the main decision-making dynamics of the experience.

The browsable version of the prototype is available in Chapter 8.

5.4 The prototype with Figma

To enrich and complete the prototype of the application, Figma was employed as a tool. It was used to build an interactive structure and UI graphics based on the prototype made with Twine, ultimately connecting all parts of the workflow from the storyline to the final visualization.

You can check out the full prototype here.

5.5 Canva

5.5.1 Canva for website design

The decision to create the website aligns with the goal of the project: to make the interactive experience reachable to more visitors coming from all around the world. It catches the visitors’ attention and takes away the doubts that might arise while choosing to benefit from an experience or not; especially if they are coming from far away.

The banner image that has been put in the hero section of the website and can be used to promote the game experience was made on Canva. Its main goal is to simulate how the visitors would feel if they could enter the Deer Cave and also what they could find there.

The pictograms that we chose as our star assets are not disposed in the real cave in that order but the choice to take them from their own walls, using tools provided by Canva and some others like Clipping magic (see section 9.3), and putting them together in that disposition, was purely to make the visitors imagine the story of the game just by looking at the still image.

The UI of the website draws inspiration from the game Firewatch and from animated films such as Ice Age and Brother Bear, which contribute to creating a warm, cave-like atmosphere. It also references The Flintstones for the design of the logo.

These choices evoke a sense of nostalgia for visitors who may have grown up with these visual references, while also adding a playful charm that appeals to younger audiences.

5.5.2 Canva for UI design draft

The UI design of objects, items, images and backgrounds was mainly done by using the user-friendly interface of Canva, both with the help of elements inside the tool and images found on the Web. This draft of the UI was used to design the prototype in Figma, with adjustments where needed, and it can be seen in the Github repository for this project at this link here.

5.6 AI

Some images (the puzzle game background, the cartoonified version of the items in the diary, animals’ pictograms from the AI quiz game — except the deer) and the figure of the Shaman were created using generative AI, specifically Gemini. This use of AI has only been engaged as a form of “first draft” ideation to visualize the plausibility of our project plan. In the case of actually implementing the game, the goal is to develop each object and part step by step and curate the design in every detail with more specific game environments and UI development softwares.

puzzle game _ _Place The Items.png)

AI quiz game _ _Listen To The Hunters 2.png)

We employed the same use of AI to generate some videos that can be seen in the Videos section of our home page. Again, this was done mostly to give life to how we envisioned the possibility of a cinematic game development of our narrative together with 3D modeling and rendering.

5.7 Set-up: Hardware, Software and Media

The following set-up is planned for this stage of the project:

Hardware

- 5 tablets with adjustable stands

- Headphones for each station

- A dedicated museum room

- Physical replicas of selected artifacts

Software

- Unity or Unreal Engine 5

- 3DF Zephyr and Blender for 3D model optimization

- Audio editing software

- User feedback tracking tools for future improvements

Media / Digital Assets

- 3D model of the Deer Cave

- High-resolution pictograms

- 2D animation of pictograms

- Evocative soundtrack

5.8 Further Development and Maintenance Issues

Potential future developments include:

- Technical updates to the game engine

- Expansion of the narrative and educational content

- Addition of languages for international visitors

- Potential conversion to a VR version

- Possible public release outside the museum environment

Maintenance will require continuous monitoring, regular software updates, and periodic checks of the tablets’ performance.

6. DISRUPTION

The development and long-term sustainability of the project must address several potential issues that could compromise both its feasibility and its preservation over time.

A first challenge concerns the economic and practical costs of reproducing or maintaining the environment required for production. Access to the necessary equipment, namely tablets and all devices needed to experience the installation, may require a budget that does not fall within the expenses foreseen by the exhibition venue.

Another critical issue involves the continuous deterioration of digital resources and the rapid evolution of technological standards. Digital materials such as videos, textures, or audio may degrade over time, suffer file corruption, or become incompatible with new software ecosystems. Likewise, software may evolve or be discontinued, threatening the project’s long-term operability. The risk is that some resources may become partially or completely inaccessible, compromising both the integrity of the experience and its potential for future updates or exhibitions. To mitigate this risk, it is essential to adopt sustainable digital preservation practices, such as periodic file migration, redundant backups, comprehensive documentation of dependencies, and the use of open or widely supported formats.

A further critical concern relates to the licensing and intellectual property status of the 3D model integrated into the project. Unclear ownership, restrictive usage rights, or missing permissions may limit the distribution and visibility of the work. To avoid such complications, it is necessary to verify the official license, obtain written authorization from the data providers, and ensure that attribution and usage comply with the required guidelines.

In conclusion, the main challenges involve economic constraints, the fragility and obsolescence of digital resources, and the legal complexity of managing licensed 3D data. Anticipating these issues through careful planning, responsible archiving, and clear legal frameworks is essential to safeguard the project’s durability and integrity.

7. TEAM ROLES AND WORK

The team is composed of Fahmida Islam, Maria De Matteis, and Martina Marchesi, students of the Master’s Degree in Digital Humanities and Digital Knowledge.

The work was distributed in a balanced way: all members participated in the various phases of the workflow, as the shared goal was to develop a coherent, homogeneous, and fully integrated project. However, based on previous studies, individual experience, and personal inclinations, each member focused more deeply on specific aspects of the design process.

From the development of the initial idea to the creation of a first prototype, here are the profiles of the team members who contributed to the project:

Maria De Matteis holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Cultural Heritage and a Master’s Degree in Archaeology and Cultures of the Ancient World. Her academic background allowed her to bring solid disciplinary expertise in Archaeology to the project and to take particular responsibility for the first phase of the workflow, dedicated to researching the historical and archaeological context of the Deer Cave through bibliographic and digital sources. This phase was essential, as one of the project’s priorities was to ensure a rigorous and scientifically reliable foundation. After collecting and verifying the necessary information, Maria worked on developing a coherent narrative base upon which the video game’s storyline was later built. She also contributed significantly to the writing of the website texts, ensuring their accuracy, clarity, and cultural relevance, and was directly involved in integrating this content into the website.

Fahmida Islam holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Anthropology from the University of Bologna and, thanks to her academic background, brought to the project a valuable perspective on symbolic systems and the cultural dynamics of ancient human communities. In terms of practical development, Fahmida was primarily responsible for building the website that collects the various stages of the project and curated the interactive narrative using Twine, shaping decision-based pathways that reflect the game’s logic. She also played an important role in producing the video trailer (using parts of the

video produced by the University of Salento that documents the creation of the 3D

model) and in editing videos and images, contributing to the audiovisual dimension of the project.

Martina Marchesi holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Humanities from the University of Bologna and supported the team especially in the revision and refinement of the storyline, drawing not only on her skills in content reworking but also on the sensitivity developed through her personal experience with video games. Her creativity proved particularly valuable in the graphic design phase: Martina worked on the development of visual interfaces using tools such as Canva and Figma, helping to define the aesthetic and communicative identity of the project. Her attention to visual coherence and user experience contributed to shaping a prototype that is both harmonious and functional.

8. UX SCENARIO

In the development of the UX scenario, Twine was used to map and visualize the interactive structure of the user experience. Its node-based system made it possible to design the flow of actions, dialogues, multiple-choice options, and branching pathways that shape the player’s journey. By structuring the narrative in this way, Twine allowed us to build a coherent, intuitive, and well-organized storyline that reflects how users will actually navigate and interact with the video game.

You can find the link here.

9. REFERENCES

9.1 Bibliography

- Benyon D. - Designing User Experience: A Guide to HCI, UX and Interaction Design, 2019.

- Cocchi Genick D. - Preistoria, QuiEdit, 2009, pp. 190-191.

- Ingravallo E., Aprile G., Tiberi I. - La Grotta dei Cervi e la Preistoria nel Salento, Manni, 2019.

- Valzano V., Bandiera A., Beraldin J.-A., Blais F., Cournoyer L., Picard M., Gamache D., Gorgoglione M. - Modellazione digitale 3D della Grotta dei Cervi.

9.2 Sitography

- Aragonese Castle - Accordo di valorizzazione

- Firewatch (benchmark/inspiration) - Project Page / Official Game Website

- Google Reviews - Deer Cave

- Preistoriainitalia.it - Deer Cave

- Video of 3D modeling

9.3 Tools